This post describes multiple ways I’ve seen projects handle event triggering in the past and suggests a minor tweak that I believe will greatly benefit projects that have nontrivial event triggering requirements. The tweak is simple and helps to avoid creating unnecessary dependencies between unrelated parts of your system.

Additionally, it also describes how a tiny domain specific language can be used in the implementation of this, trying to make it possible for even non-developers to manage and create event triggers. Perhaps even using a visual tool! I never got this far in my own implementation, but it’s a very obvious next step from where the post ends.

The ideas discussed here aren’t new. The functional outcome of my ideas have been available in various SaaS solutions for probably a decade. Nonetheless, I think there’s an important lesson here regarding software in general, in how seemingly minor changes in structure can have outsized benefits when it comes to the cost and complexity of developing and maintaining a system.

Before we really get going I want to note that, although we’ll be talking about sending emails, the point I’m trying to make is much more general. It just so happens that notifications are a very natural context to describe this problem with. Every time I’ve tried to explain these ideas, I always end up going back to notifications.

A final thing before we continue: I’ll need a pinky promise that you won’t use this to spam people. No. Yes, seriously. Spam is easily top 3 on the list of the 7 deadly sins.

We good? Alright.

The problem

On most projects I’ve worked on, it has at some point been a requirement to trigger certain functionality when specific events happen. A classic example is “send an email to users who haven’t used feature X within their first week of signing up”.

Even though this example is rather basic, it can be surprisingly difficult to implement well. If we’re not careful when we implement event triggering, we can inadverdently start introducing dependencies between otherwise unrelated components, which over time can become a burden that slows development significantly. What once started as a simple one-liner to send an email can suddenly require that we have to consider large parts of the system whenever we want to make even a small change.

Simple triggers

At the beginning of a project there isn’t a lot of functionality yet. This hopefully means that there aren’t a lot of accidental or unnecessary dependencies between components, and that it’s still pretty cheap and easy to add new features and maintain existing ones. Not wanting to introduce new abstractions before they are truly needed, at this stage it can easily be argued that sending an email when a user is created is most simply done somewhere on the code path that naturally exists for user creation. This could, for example, be just after the user has been persisted to storage:

class UserController:

def add_user(self, user):

self.user_repository.create(user)

self.email_service.send_intro_email(user)

Depending on the full context of the rest of your system, the project’s goals and scope, your team and the position of the moon, this very well could be a nice and simple, non-overengineered solution to a simple problem. Lovely!

A benefit of this simple solution is that it’s easy to look up what happens when you add a user: it’s all right there in the add_user() function! This of course comes with the assumption that everything that happens when you add a user actually happens in that function.

Depending on how many event triggers we need to implement, a potential drawback of this simple implementation is that we will be scattering email-sending code all over the system. This might make it difficult to get an overview of all of the places from which we’re sending emails. Although this could become a problem, the thing that tickles my spidey sense is that there are examples of reasonably simple event triggering logic that simply cannot be implemented this way. At least not in any advisable way that I know of. Triggers that require more information than naturally exists on existing code paths are super difficult to implement without introducing coupling between otherwise unrelated components. In the above example we wanted to trigger on the “user created” event, which happened right there in the code. For more complex triggers such a code path might simply not exist.

More advanced triggers

As time passes and new and more complex features are added to the project, we might want to create event triggers that aren’t a direct response to something that happens in the system. Such event triggers rarely have an obvious location where we can just add a one-liner. The problem is that we need knowledge from different parts of the system in one place.

One obvious way to tackle this problem is to create an omniscient cron job-thingy that can pull information from all relevant parts of the system. In my mind I imagine this as an octopus that gets to roam around freely in your database, sticking its tentacles into anything it likes.

The benefit of this strategy is that it can make it very explicit what information is required to trigger a certain event and where that information comes from. Additionally, depending on our needs, it might be an advantage that this allows us to place all code relating to sending notifications close together instead of sprinkling it throughout the system. Below is an example of what this might look like:

class OmniscientCronJobThingy:

def x_not_used_in_first_week(self):

for user in self.user_repository.list(created_within='1 week'):

if not self.feature_x_repository.used_by(user):

self.email_service.send_feature_x_intro_email(user)

Since this is a cron job we have to run it at some meaningful interval, ensure that it actually runs, probably handle errors asynchronously (we don’t want stop sending emails to the rest of users just because sending an email to one of them fails), and so on. All of these are problems that can be overcome, but it does come with the price of added complexity compared with the one-liner we first saw.

A major drawback that our omniscient octopus introduces is that it adds a dependency on potentially the entire data model of the system. Since it’s basically a component with license to kill read data from anywhere, we have to take it into account whenever we consider making a change to almost literally any part of the system; did one of our co-workers add an event trigger that requires knowledge from the part the system we’re currently considering changing? This problem can be mitigated somewhat by forcing the component to go through epositories instead of raw-dogging the database, but this doesn’t eliminate the problem entirely. When there’s an omniscient octopus tasting various parts of your data, you never quite know whether it’s safe to change your data model or not. At the very least, the loose octopus will make it more cumbersome to change the data model. Been there, done that. Although pets are nice and cute, you really don’t want them running around your database!

Another problem we haven’t discussed yet is that of using existing data models to infer the state of something that we want to trigger on. In some cases we’re lucky that the data model naturally happens to contain exactly the information we want to trigger on. In other cases, not so much. What do we do then? Do we muddy the existing data model by adding just one more field, to keep our omniscient cron job satisfied? I would personally be looking for different options very quickly.

To summarize: we are looking for a solution that

- avoids sprinkling email-sending code all across our application

- avoids unwanted tentacles fiddling around our tables

- does not create unnecessary dependencies between components

- does not lead us into the temptation of introducing “unnecessary” data into our existing data models

As advertised earlier, the path I’m suggesting is in no way new nor sophisticated. It’s fundamental programming. One of the classics. It’s decoupling.

If we simply separate tracking of events and reacting to events, we can have all of the benefits from our two solutions with very few of the drawbacks. We might even be able to move a large part of the human responsibility for declaring event triggers to non-developers!

The following snippet looks very similar to our first one-liner snippet, but the result is quite different.

class UserRepository:

def store_user(user):

self.user_repository.create(user)

self.eventdripper.log(

event_id="user_created",

entity_id=user.id,

data={'name': user.name, 'email': user.email},

)

Although there’s a new name here that I haven’t introduced yet (eventdripper - yay naming!), there are no tricks and it should be fairly obvious that by logging the occurrence of an event instead of reacting to it immediately, we can move the responsibility of sending emails away from the place that the event naturally occurs. In this case, the responsibility has been moved to the mysterious Ms Eventdripper.

Besides delegating responsibility, another benefit of logging events is that we no longer need to keep our handsy octopus on staff. Since eventdripper is given all information required to determine which event triggers to trigger, we no longer need an omniscient entity that can snoop on the existing data model to gather information about the current state of things. This also avoids the temptation of adding new fields to our data models just to satisfy the needs of our snoop.

As you might have guessed from the poor naming, I’ve implemented a service that makes it easy to log events and react to them later. It tries to solve the problems described in this post, and it works for complex event triggers with restrictions on real-world timings. That service is called…. Eventdripper!

Eventdripper

As indicated by the snippet above, the interface of eventdripper is dead simple:

POST /event

{

"event": "user_created",

"entity_id": "user-id",

"data": { /* data relevant when reacting to the event */ }

}

All the information it needs to do its magic is:

- the name of event that happened

- a unique identifier for the entity the event relates to

The third parameter, "data", is an optional, opaque value that the consumer can use to add metadata needed when reacting to the event. In our example, since we’re sending an email, it might be nice to have the user’s name and email.

In order to get data into eventdripper, we just have to send the above payload over our preferred transport (Seb anyone?). Eventdripper then collects the events and shoves them into a database, indexing them on "event" and "entity id". For the purposes of this post, the way data is transported and stored isn’t super important. As long as events are received in-order and the database allows fast lookup by event and entity id, we’re golden.

With all of our events now happily inhabiting the databases of eventdripper, we have a new problem to solve: how do the users of eventdripper describe which sequences of events that should satisfy a trigger? And, related to that, how does eventdripper decide whether the user’s description is satisfied by a given sequence of events? If you’re anything like me, hearing these requirements simply begs for an implementation of a domain specific language. This is the story of how driplang was born!

Driplang

Driplang is a tiny, domain specific language (DSL) inspired by boolean and temporal logic. The DSL makes it easy (okay, possible at least..) to define expressions that can either be satisfied or not by a given sequence of events. A driplang expression can’t be evaluated by itself, but must be evaluated against a sequence of events.

Driplang has four operators: AND, OR, NOT, and THEN. The two only possible outcomes of expression evaluation are true and false.

The driplang operators work just like you would expect them to in boolean logic, with the caveat that THEN is (very) special.

Let’s start by looking at a few simple boolean examples. The contents of this table shouldn’t be surprising if you already know boolean logic.

| expression | events | output |

|---|---|---|

A AND B |

[A] | false |

A AND B |

[B] | false |

A AND B |

[B, A] | true |

A AND B |

[A, B] | true |

A AND (NOT (B OR C)) |

[A] | true |

A AND (NOT (B OR C)) |

[B, A] | false |

A AND (NOT (B OR C)) |

[D, A] | true |

The important point to notice here is that the order of events doesn’t matter for AND, OR, and NOT.

As the name hopefully suggests, the THEN operator is needed when we require a ordering, e.g. if we only want our expression to be satisfied when A happens before B. In driplang that requirement would look like this: A THEN B.

Here’s a table to give you an intuition for how THEN works. I left a tiny surprise for you at the end.

| expression | events | output |

|---|---|---|

A THEN B |

[A, B] | true |

A THEN B |

[B, A] | false |

A THEN (NOT B) |

[A] | true |

A THEN (NOT B) |

[A, B] | false |

A THEN (NOT B) |

[A, C] | true |

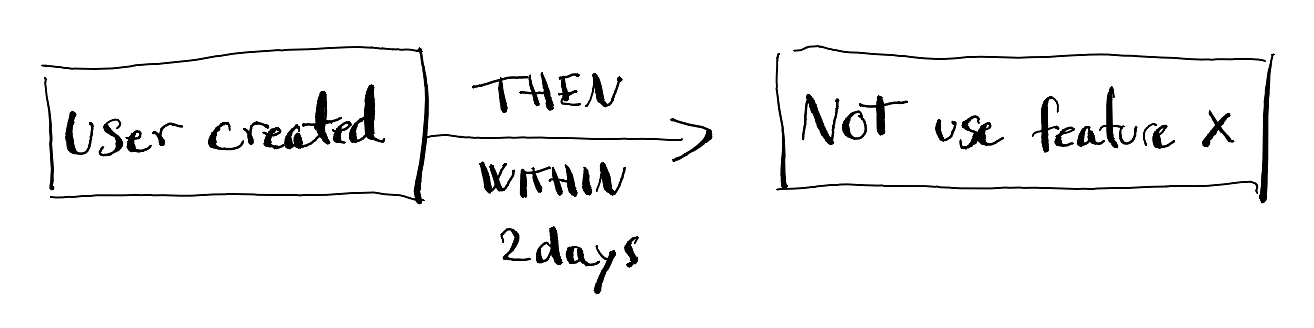

A THEN (B WITHIN 2 days) |

[A, B] | it depends |

Hopefully everything makes sense until the last expression in the table above.

A minor but very important note that I left out, is that THEN has an optional argument: WITHIN. WITHIN causes THEN to consider real-world time. This means that, besides the fact that the events must arrive in the required order, they must also have arrived within the given time constraint. The expression A THEN (B WITHIN 2 days) from the table above will thus only be satisfied if B happened within 2 days of A.

All the way in the beginning of this post, we talked about triggering on events based on real-world time: “send an email to users who haven’t used feature X within their first week of signing up”. WITHIN is the piece of the puzzle that allows driplang to handle this. We now know enough to express this as a driplang expression: user_created THEN ((NOT use_feature_x) WITHIN 7 days).

A great benefit of using a DSL to implement this is that it can be used two-fold: we can use it both to describe describe event triggers and to evaluate them. And, since driplang is easily expressed as text (via a stupid-simple JSON format), we can easily store driplang expressions in a database, close to where the events we need to evaluate them on live.

As I hinted at in the beginning, this post ends at a point where the obvious next step is to make a visual tool that can generate driplang expressions behind the scenes. I’m no UX designer, but I imagine it might look something like this:

I think this could be helpful by letting non-developers, who often are the people that declare the trigger requirements anyway, be responsible actually managing event triggers. This would leave developers “only” with the job of logging events and implementing the functionality that must be triggered. In my experience, the functionality to be triggered (sending non-spammy emails) can often be abstracted enough that developers don’t have to be part of this in the long run, e.g. using email templates with variables.

Performance and implementation

In terms of performance, there’s a few things we can do to optimize scheduling of expression evaluation; for expressions that don’t contain THEN operators with ‘WITHIN’ arguments, we only need to evaluate expressions when a new event is added; the only time that the output of these expressions can change is when a new event arrives.

Additionally, we only need to evaluate expressions that contain references to the event that just arrived. For example, the expression A THEN B will not change if the event C arrives.

So even if we have loads of event triggers declared in eventdripper, waiting to potentially be triggered, we only have to evaluate the expressions that contain the new event. With a bit of semi-clever SQL, we can ensure that we only evaluate expressions when there’s a chance that the output changed.

The only type of expression we haven’t considered yet is THEN expressions with WITHIN arguments. Here, it’s not only the arrival of new events that contributes to whether an expression is satisfied, but also the fact that time continues on its infinite march. I don’t currently see a way of doing this that doesn’t rely on a cron job having to run in the background, reevaluating expressions at some fraction of the interval of WITHIN’s time constraint. If you’ve got any ideas for how this could work, do reach out!

Although the implementation of eventdripper and driplang is interesting to discuss, I’ll leave these details for another blog post. For driplang, however, I will say that it requires surprisingly little and rather simple code, especially considering that it allows us to both describe and evaluate rather complex event triggers which otherwise have a tendency to turn into a big ball of mud.

Heading back to the surface

Having just been introduced to eventdripper and driplang, you might be thinking that this looks like an overly complex solution to something that in many cases can be solved much simpler, with code closer to the first snippet I showed. In situations where your needs are simple and you don’t expect to need more advanced triggers, I most likely will agree with you. In general we should not waste time overengineering things that we will not need.

The one thing I hope you take away from this: once your event triggering needs become non-trivial, I think decoupling the code that tracks and the code that reacts to events is definitely worth your while. Whether you use a DSL to implement this is another discussion. So far, it has served me well and helped solve exactly the problems I set out to solve. I’m very happy with the results!

If the post resonated with you and you are looking for someone to help you to do hard things with a computer, you can hire me to help you!